In my first post I highlighted how much better the world has become over the past few generations. This is a certainty and a reality. We live, essentially, in an age of miracles. Yet, somehow, in this age of technological expansion and widening economic growth, growth itself is a word rarely used by political activists or politicians. There may be a passing mention of economic growth - but the purpose of that, beyond a promise of jobs - is left unsaid. In fact, there is so little sensitivity to the importance of growth that the drivers of growth are viewed with suspicion, or downright distaste.

That we want more connectivity for greater communication of ideas, that we want easier and cheaper transport, more technology, more humans and less processes to block innovation are nearly all frequently considered for their ills. We hear little of the benefits of texting, emails, zoom calls and more of what they have supposedly taken from us. Similarly, we see protests against new roads, new rail or new runways, constant suspicion of new technologies, direct calls for fewer children and ever increasing bureaucratic levels of checks and balances on large-scale projects. These are all examples of accidental, or sometimes even direct, DeGrowth Mindset.

DeGrowtherism or DeGrowth Mindset is a set of background assumptions and beliefs that portray a deep suspicion of policies of growth. DeGrowth Mindset is related to Cheems Mindset (the idea that something shouldn’t be done because it is hard to do) but rather than hamper growth through discouragement and obstructionism, DeGrowtherism is opposed to growth - either by default, or on purpose for other ends.

DeGrowth Assumptions

Wealth is Stagnant

The popular image of growth is that there is a finite amount of wealth in the world, which is either “hoarded” by the mega-rich or yet to be “re-distributed equitably”. This is why the pie analogy of wealth is so popular. If you haven’t heard the analogy it goes something like this: the economy is a pie, rich people have 90% of the pie, everyone else fights over the rest, with the largest number of people receiving crumbs or even (in one version) none of the pie - they just hold the debt for it. The fact that the pie can grow bigger and everyone get richer (even if you remain unequal in wealth) is ignored entirely by the analogy. In fact, the pie analogy of wealth is a great sign of just how stagnant people tend to assume wealth is.

I think this is also why so many people are suspicious of the claim that increasing wealth has reduced poverty. They understand that the modern world is infinitely better for medical care than the past, but they do not believe that absolute poverty can be eradicated, or is somehow already rapidly reducing. Instead, the image is that the West hoards wealth and exploits others - and that the super-rich exploit everyone else. The pie doesn’t grow - we just all shuffle the wealth around.

This viewpoint is clearly inaccurate - and it is also inconsistent with other popular beliefs - but this doesn’t stop it being an assumption widely held. Beliefs do not have to cohere with one another, especially if everyone else around someone believes the same (or similar) set of conflicting or contradictory beliefs. The wealth is stagnant viewpoint is a key assumption in DeGrowth Mindset. Growing the economy, creating more jobs, building more infrastucture - these are all policies that just aide the rich. The question isn’t “Will this policy bring growth and innovation?”, it is instead “Who gets rich off this policy, and at the expense of who else?”. This is a foundational part of DeGrowtherism.

Technology is Suspect

However, whilst wealth may be viewed as stagnant - a jostling between the rich and poor - technology is actively viewed with suspicion and this suspicion feeds a DeGrowtherism-by-default Mindset.

We see a form of this in nostalgia posting. The belief is generally that things were better in the past, especially during the poster’s own childhood - a time in which, coincidentally, they had their youth and career choices still ahead of them. But it is actually more than just this - it is a belief that the lack of technology and options in their childhood meant that their childhood was superior to modern childhoods. In other words: technology has made childhood less enjoyable, less real and actively worse.

I mostly think that these kind of views can be better categorised as “cope” and fear. They’re a cope against the fact that the older generation are, indeed, older and if their childhoods were also worse than modern ones, they lose that cope to soothe the realities of aging. They’re also a symptom of a fear of the current world and the new threats it has for children, which are different to the old threats. For instance, children today are over enthused by youtube videos of colourful animals and spend too much time texting, whereas children in the 50s merely had to play outside and occassionally die of polio.

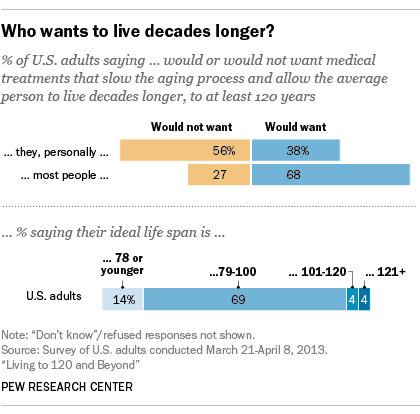

Technology is bad and suspicious - the past is better, simpler and somehow more real. This is not, however, confined to bad pie analogies or nostaglia posting. On a recent (2019) survey of 34 000 people, across 28 markets, 60% considered that technology was “moving too fast”. Even more astoundingly, a striking amount of the population does not support the extension of human life beyond its current average length.1 I believe, again, this is best described by cope (if people in the future live 200 years, but we average around 80, its psychologically better to believe that 80 years is somehow the “right length” or the equitable amount of time to exist, rather than admit that it sucks I wasn’t born when the average climbs to 200). It is also equally described through fear of the unknown - we don’t know how future technologies or life extension may work, be used, effect jobs or relationships or governance etc.2

This deep suspicion of technological growth - and growth in general - can be seen most clearly in artistic representations of the future. Sci-fi, with the notable exception of post-scarcity Star Trek, is filled to the brim with future dytopias. There is an entire teen fiction genre constructed around dystopia. Utopias are generally just not as interesting a narrative device - but the effect is that our popular visions of the worlds of the future are often filled with too many people, crammed into small living spaces, existing in squalor with rich overlords, technology is used to de-humanise, corrupt or for population wide survelliance. The future is a place where teens compete for food in battle arenas, or robots rebel against their human masters, or the sun is never present under the large tower blocks crammed with squalid lives, or….

The future is rarely a world without poverty, without disease, with less human and animal suffering and a world of billions living in green cities, with cheap widespread space exploration and easily-accessible virtual worlds filled with entertainment and human connections. This wouldn’t be good for narrative purposes of course, but the image it portrays of our future is a clear De-Growth by default worldview. These are places with stagnant money, where the rich hoard it and poor starve eating re-purposed humans for their sustenance. Growth - be it technological, economic or a growing population - leads inevitably to dystopian worlds filled with cruelty, corruption and poverty. It is, in fact, the opposite to what we see play out in reality. But it is the world I think many people find themselves fearing - or even expecting - by default.

“We Are the Real Virus”

DeGrowth Mindset - DeGrowtherism by default - may be popular, but it is actively fed by dedicated DeGrowthers. These are people that actively argue, consciously, for the cause of DeGrowtherism.

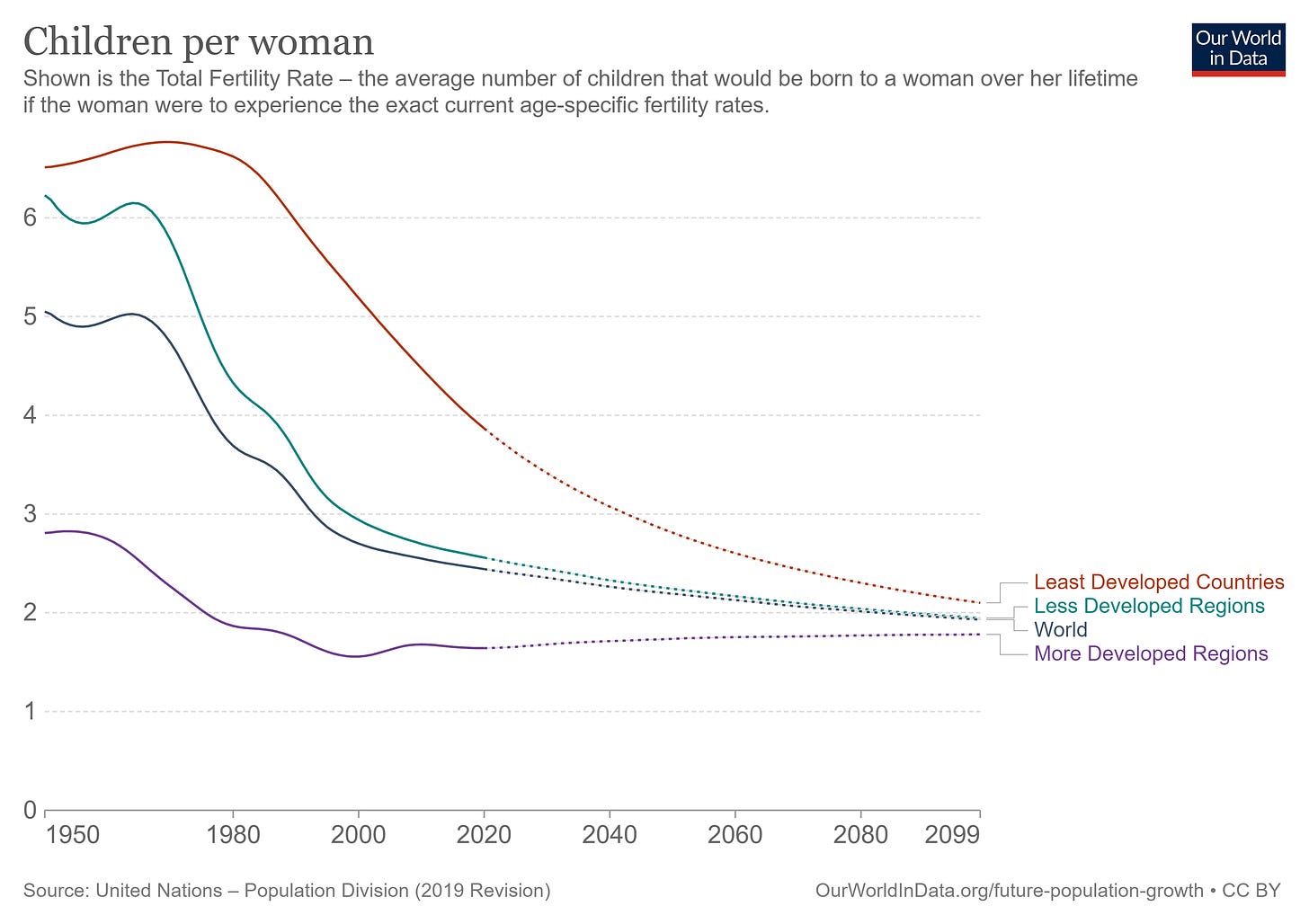

Climate Change activism is perhaps the most textbook example of active DeGrowther Mindset, especially when it comes to growing our population. One of the best drivers of innovation and economic growth is the increase of people. People provide ideas, people live valuable lives, and people produce the next generation. However, this viewpoint is far from the most popular.

Instead, the popular worldview appears to be that humanity is a net negative; a carbon-causing, rainforest-destroying, corrupt bulldozing species of predators - a nasty virus that is harming the planet. It is this view that helps feed the modern rejection of having children. This is more likely a consequence of the cost of housing and child-raising which is morally ret-conned by many of us into a difficult choice for reasons of the “carbon-cost” of a child’s life. But we don’t have to go very far to find the view that future human-lives should be reduced in number. “The Biggest Threat to the Earth? We Have Too Many Kids”, “Should We Be Having Kids in the Age of Climate Change?”, “The Biggest Thing Holding Me Back From Having Kids is Climate Change” and “Would you give up having children to save the planet? Meet the couples who have” are some representative pieces of this genre. Indeed, in “A Life on Our Planet” whilst David Attenborough is somewhat pro-innovation, even he praises the disastrous Japanese birth-rate trend, and the wider trend of falling birth-rates across the world.

We live in a time long after the incorrect estimates that humans would soon out-number the food supply. Those estimates failed to imagine the technological leaps we would make to produce more food, more cheaply. And these fears come at a time in which we are seeing a global reduction in fertility. We are in a crisis of declining humans - not in a world of over-population. But DeGrowth mindset rejects this view; more people means more housing, more food and more water - and it necessarily equals more carbon. This is not just a climate change viewpoint, but plays into the wider assumptions of DeGrowtherism which are so popular. For instance, better technology may have saved us in the past, but we should be deeply suspicious it can do so in the future.

Climate change is a genuine crisis but opting for declining birth-rates reduces the number of people who may discover the technologies we need to get us out of this - and to do so without losing the incredible world we have been building generation by generation. Less infrastructure, fewer connections, fewer cheap foods, fewer houses, a more expense existence, fewer humans, less growth, less carbon. The fact that this also means less innovation and an ultimately poorer world, is entirely lost. This is because DeGrowtherism is far more popular than its opposite: a conviction in progress.

Progress and DeGrowtherism

A final word can be given on advocating for Progress and the rejection of DeGrowtherism. Whilst it may be more popular to be suspicious of technology, to believe in wealth stagnation and the negatives of more humans - progress is not an alien concept to popular imagination. Social progress is widely acknowledged as a reality. We do not tend to see popular arguments that diversity was better in the past,3 or that the last 50 years has made life worse for minorities. Social progress is taken as a clear truth, and one that must be defended.4

It is also the case that, whilst most technologies are viewed with suspicion, medical advancements are nearly always an exception to this (even covid-19 vaccines, which - for all the supposed controversy - were completed in record time, with minimal process and had monumental uptake by the general public). These examples are both areas of great public concern and care, which should give good hope to those of us that care for growth and the future of humanity. It is not that DeGrowtherism is necessary - that people need to feel that the world is worse in order to improve it. Belief in progress can also cause that same feeling of improvement, but also a desire to protect what is already here, what we have already achieved.

DeGrowth Mindset is pervasive, but it is not absolute. Years of stagnant or minimal growth in Britain has certainly contributed to DeGrowtherism here. So has a lack of understanding of the rapid life-changes possible through economic growth when witnessed abroad. The West sees so much of the world through appeals to charity, or updates on news stories that cover only the disasters. There is a blindness to the incredible changes possible - a blindness that will hold us back the longer we refuse to take note of its existence.

Innovation can be its own cause for action - we can use it to improve ourselves, our lives and our civilisation. The world really is better than the past, the economy really can grow to the benefit of everyone, children really are a good thing and we really can improve the future through technological innovation. DeGrowtherism can go the way of so much in our past: confined as a relic, an oddity - an historical mistake.

The immediate link I used here (from 2012) is particularly bad (60% of respondents) - some surveys have seen as low as 25% (especially when clarifying that it would be a healthy life), another study has the figure at 44%. The shock, to me, is that so many are content with the semi-random allocation of 80 years of life - the natural limit we have found with current medical technologies.

This is reinforced somewhat by the same survey that finds that those with more self-reported understanding of “emerging technologies” have higher trust in those same technologies. I’m not completely convinced by this though - self-reporting understanding has enough issues around it that I would rather relegate this to a point of interest.

Though there are some exceptions

The language of “erasure” is in part social justice activists ensuring that the clock is not wound back to a time in which minorities (sexual or racial or otherwise) were oppressed and their experiences erased - though there is more to this language than just that.

Bravo! Nicely written. I see a lot of people paying lip service to degrowth but wonder how many are actually shorting the market?

Hoping its just a passing phase

Thoughts on deGrowth: If the developed world fertility converges with the developing world ("dysgenics"), progress simply disappears (intelligence and civility has a large genetic component). Therefore it is much more logical to deGrowth the developing world through Malthusianism to maintain progress. Contraception simply is rejected by the cultures of the developing world (e.g. Ugandan Condoms), however other forms on developing world deGrowth is considered a form of colonialism and genocide, and simply castration of the educated is both easier and favorable.